A CMO'S Guide to Sticking the Category Design Landing

CMO Crowdstrike, former Category Designer in Residence at Play Bigger

Congratulations. You’ve done everything right to design your category: articulating the category problem, illustrating a vision for the future and your unique answer to it, and aligning on a category name. Your POV is pitch-perfect and feels like you finally have the story that has been buried inside your head.

You are ready to present your category vision to the world - a category which you will define and dominate. You are now ready to execute your lightning strike, sit back, and watch the market magically adopt your POV vision and category, right?

Think again.

This is where the work begins, not ends. Your mission at this stage is to mobilize the entire company and codify all of the category decisions the team has made into the fabric of the company, from product strategy to company culture. Now the fun starts to re-shape and condition the perceptions and beliefs of your prospects and customers, press, bloggers, analysts, investors, etc., taking them from the old way to the new way of working or living. Category design is a business discipline that takes time (years) and commitment from the entire company to execute, which is why it’s not for the faint of heart.

Inevitably, gravity will set in and attempt to pull the organization back into its comfort zone. Gartner doesn’t buy into the vision right away, so someone will suggest you just go back to the way they already define the market. There are competing priorities on the product roadmap. There is a marketing calendar in place and the team doesn’t want to remove anything from the plan. Category design needs persistence and patience. It means creating a line and anything that doesn’t align to the new vision falls off the plan. Letting go of the past way of working is a hard thing to do - in a way your company is going through a similar process that you are asking the market to go through, transitioning from an old way of working to a new way of working. For category design to be effective over the long-term, it needs the full commitment of the entire executive team, starting with the CEO, and it becomes the north star for the company, product and go-to-market strategy that permeates through every layer of the company.

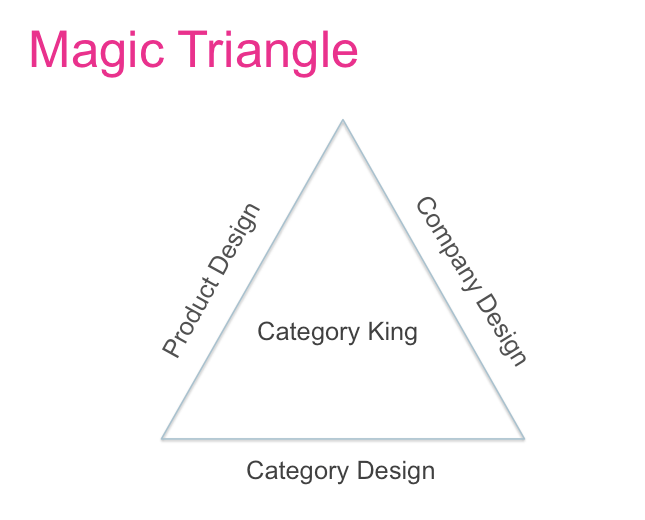

As a CMO who’s been through the category design process before, I’ve seen it done right - and I know the pitfalls to avoid. Any CMO who has gone through this process has likely seen the warning signs that indicate gravity is pulling on one or more sides of the category triangle. My mission as an enterprise software CMO is to share my learnings and experiences with my fellow brave souls embarking on their own category design journey to help maximize the chance for long term success. This is written through the lens of my experience in the enterprise software industry, but there will be gravity and pitfalls along the way regardless of your industry. The key is to know what warning signs to look for and how to put the right things in place upfront to identify and fix them before they become blockers to your success.

So how do you know if trouble is on the horizon? In my experience, the warning signs look something like this:

-The CMO is the only one evangelizing the category: I’ve lived this one. This is the tell-tale sign that the category is not supported by the CEO, since she is ultimately the Chief Evangelist. If you are a CMO and your CEO either doesn’t want to be involved in the category design process or once a decision is made expects the CMO to ‘just do it’, then it’s not a company strategy, and certainly not category design. It’s a marketing campaign. It may have legs for a few quarters, but gravity will set in. The CMO will get fatigued standing on the mountain waving the flag alone. The next shiny message will take hold. And there goes your category.

-The product roadmap doesn’t shift: This one is hard for the CMO to control if they don’t own product management, which most of the time they don’t, but it’s imperative to fulfill the category vision as you will never have every feature or capability to fulfill the vision on Day 1. There will always need to be a balance between bottom-up product feedback from the customer and top-down product strategy to fulfill the category vision, so if the only items making their way to the roadmap are bottom-up and it’s starting to look like a ‘bag of doorknobs’, then you have a gap.

-Sales is reverting back to their old talk track and tools: This one is inevitable. Marketing creates a customer presentation that is a visionary masterpiece. A work of art. Then sales changes it. There will always be an element of sales customization of content to make it relevant to their specific deal, but it’s a slippery slope from content customization to outright abandonment. It will happen so the key here is to catch it and contain it early.

The key is to watch for these warning signs and to course correct early. Here are some rules for sticking the landing of category design to maintain balance and alignment on each side of the triangle, both from my experience as a CMO and seeing the category design process in action with Play Bigger.

Rule 1: Don’t Over-Rotate

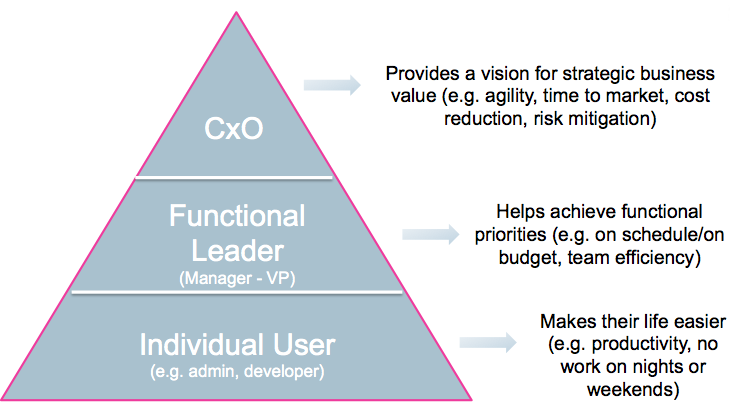

What is over-rotating, you ask? We’ve all done it. You’ve done something one way, realize it’s either broken or no longer enough to achieve your goals, and then you put a new strategy and plan in place. Then you realize you went so far in the other direction that you completely abandoned the old way, and you actually needed to do both. You needed an ‘and’ not ‘or’ strategy. Go-to-market strategy is a common offender of the over-rotate strategy. Your company started with a bottom up strategy, selling a point tool to an individual user. Then you realize you need a top down enterprise strategy which gets to the executive level. So all of your messaging, product and sales motions focus around the top-down motion, yet you forget one little detail: the individual users make up a significant portion of your existing revenue. So you keep the top-down strategy but integrate the old bottom-up strategy in tandem. Over-rotation. The category and POV tell a narrative about why the world is changing and the old way is no longer sufficient. A new category prescribes a new way of working or living, and in the case of the enterprise may prescribe a new discipline, cultural shift or organizational change. The outcome of a category drives strategic business value and will ultimately become so important to the organization’s success that it becomes a line item on the budget. It’s natural that the category vision aligns with the C-suite and executives within the organization and enables you to have a strategic business discussion, but what if you sell to users or first line managers today?

Category design shouldn’t alienate the loyal base that got you to this point, so for the category to stick it’s important to connect the vision at every level in the organization. Bring every person, team, or function that cares along with you on the journey. For example, the category vision may deliver an outcome of agility and time to market, cost reduction, and/or business risk mitigation for competitive advantage, all of which are important to the C-suite but may not resonate down to the people ‘in the trenches’. From here, you need to link the category vision to functional leaders and the users of your product. Explain how the category vision and the underlying technology helps them achieve their objectives, makes their life easier, or makes them the hero.

Make sure to create persona-based narratives which resonate at each level, but are connected up to the category. Without this, you may find you have a killer category POV talking to an audience you are just building a relationship with, which drops directly down to a product-led sale where you sell today, and the two motions are completely disconnected. When this disconnect occurs, your sales team will start reverting back to the product and transactional talk track - think features, functions, and why your tool is ‘better’ - and you never get the mindshare at the CxO level. WIthout the buy-in at all levels, your category is dead.

Once you have the POV narrative on paper, which is likely the CxO message, create a persona-specific POV for each relevant persona. This could be by function, role, or title/level. Elements to include for each persona-based POV:

Problem: A short statement which frames the problem (the ‘from’ state), aligned with the category POV. Include supporting statistics and data points whenever possible.

Ramifications: What is the impact of not solving the problem for this specific persona.

Vision: What are the requirements or capabilities required to solve this problem (which only your solution offers).

Solution and Outcomes:

-What are the platform components of the solution and customer use cases supported, based on your product blueprint.

-How your company and solution uniquely solves the problem and why you are the best strategic partner help solve it.

-What are the business and technical outcomes (the ‘to’ state).

Customer proof points: where else has it been done and what was the outcome.

Persona Elevator Pitch: Your boilerplate which summarizes the above and is used as the standard description for any persona or use case specific content.

In the Play Bigger community there is a great persona-based message house template you can download to help get you started at www.categorydesigner.com.

Rule 2: Avoid the Swiss Army Knife Syndrome

The swiss army knife. It’s the enemy of category design. It’s also one of the top signs you are in need of a category to create a container for the product strategy and product story. When you hear comments such as, “It’s great because it can do everything!” or “What would you like to see?” in a first demo with a prospect, you have a category design gravity problem mounting. When this occurs, the sales team lets the prospect drive the meeting and determine what and how they see the technology solving their problem (translate: they are positioning your technology vs. the other way around) and/or new product releases don’t have a clear path to either fulfilling all of the requirements to dominate a market or logically expanding into new markets. Category design creates the container to shape both the product strategy and the sales motions, creating new ways to monetize the platform and scale the business.

A common product strategy is to evolve from a tool to a platform. Point tools usually do one thing well and are used by individuals to solve a specific problem, but are not typically viewed as strategic to the organization. Platforms, on the other hand, are sustainable and viewed as long-term investments to the organization given they help solve multiple problems for potentially multiple people in the organization and are flexible to integrate with other tools in the ecosystem. While a point tool solves specific use case, a swiss army knife can be positioned as the answer to the category problem. The foundation of the platform, which may start as your point tool offering, becomes the base for the platform. It could be used as a way to seed the market as a freemium offering, deposition other point tool offerings that aren’t part of a larger platform, and is common functionality and IP which powers the applications that are built on top of it. The applications are purpose-built to solve a problem for a specific persona, which could include custom content, workflows, or reports specific to the use case, creating monetization opportunities as the company scales. It also provides a blueprint for new application development, partnerships or acquisitions, with every new application clearly showing how you are fulfilling the category vision and cementing your leadership.

When I was CMO at Coverity, now Synopsys, our category vision created the container to evolve the company from a tool to a platform - and in the process significantly increase average deal size and become a strategic initiative to the VP of Engineering and CTO. Coverity was founded to create a commercially viable static code analysis technology. With Coverity, developers could quickly scan millions of lines of code within their development workflow to flag defects in their code. The initial messaging was focused on the science behind the technology and showing developers cool defects in their code. Coverity was a hit with developers, but static analysis wasn’t a strategic investment which garnered the attention of the VP of Engineering or the CTO and without management buy-in it was not only a low level purchase price but also a renewal risk. Category design enabled us to expand and evolve the message from the science of static analysis to the business value of finding software defects earlier in the development cycle. Development Testing. Development managers cared because they were responsible for getting the project out the door on time and on budget, and defects identified late in the process posed a risk. Development and business executives cared because the risk of finding a defect late meant the release was delayed, which actually created a time to market and competitive risk, or worse a defect escaped in the field which resulted in lost revenue and customer trust, or worse if in a safety-critical device.

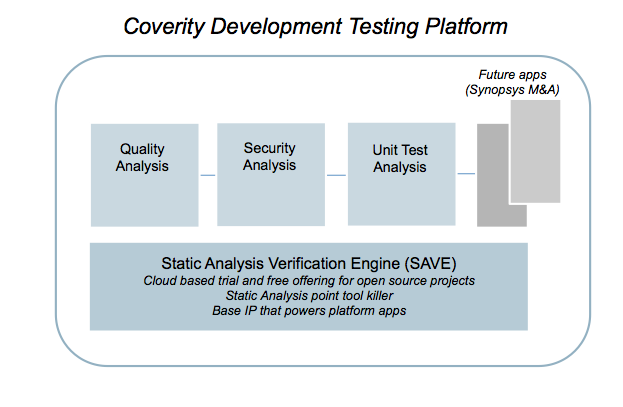

Development Testing as a category caught on in the market. To support the category vision, we created a Development Testing platform, powered by the static analysis engine. The category vision was that developers need to be armed with technology to test their code in their workflow, so any element of code testing would be integrated or built into the platform. We built modules on top of the static analysis engine, starting with Quality Analysis and then expanding to Security Analysis and Unit Test Analysis. Since the acquisition by Synopsys, they have made a number of acquisitions which continued to fulfill this vision, expanding out beyond Development with an even larger category vision of Software Integrity. By moving the static analysis technology into the foundational engine, it still kept the foundational technology and IP the company was founded on as part of the story, but in the process de-positioned other static analysis point tools in the market. Security Analysis enabled us to move from the embedded software market to the ISV and enterprise IT software markets which significantly expanded our Total Addressable Market (TAM). By creating additional monetization opportunities with each application on top of the platform, average deal size increased and we created additional up-sell and cross-sell opportunities.

As you move along the journey from tool to platform, make sure to get alignment on the product roadmap on two fronts. For the markets you play in today, identify and prioritize the gaps required to fill any functionality gaps for the key use cases relevant to that market and get commitment on the roadmap through a combination of build, partner, or buy strategies. For new product introduction, look at the TAM once the category vision is fulfilled versus what portion of that TAM you can achieve with your current product set. Then prioritize which applications to build or buy based on their revenue impact in terms of up-sell and cross-sell in existing markets or new market expansion. With each product release, the marketing team has a drumbeat of air war and ground war momentum to show how the company is realizing the category potential with each release, and leaving the competition in its shadow.

Rule 3: Create a Content System of Record

Sales will always need to customize their content for a specific account or deal, so instead of trying to fight the inevitable and the necessary, marketing should partner with sales to create a core set of compelling and relevant sales tools and content which articulate the category vision and should be the front section of every first presentation, demo, or touch point with your company. And every salesperson needs to get certified on the pitch. One of the biggest cultural shifts in an organization as a result of category design is transforming from what may be a functional, tactical talk track to a strategic, business value conversation. The category POV should be able to keep a salesperson in the CxO’s office for at least an introductory meeting. With this transition, some salespeople will be able to make the leap and some won’t - and that’s ok. What category design process transformation will do is create a consistent narrative from which to frame the problem, articulate your company’s vision for the future, and the outcomes for your customers by solving it (with your technology). Certification is a critical component of this process, as it will identify the salespeople who may not be able to make the leap early - they are the first people in the organization who will revert back to their comfort zone of product-feature focused messaging. This entire process will create the right alignment and accountability between sales and marketing from the beginning of the process.

To create a standard content bill of materials, think about the first touch points that a prospect, analyst, journalist, investor, or any other relevant stakeholder has with your company and make sure the category POV is the story and message of these assets to frame every touchpoint that follows. Key assets to include in the bill of materials include:

-Customer facing presentation and script

-Company overview and solution briefs

-Product demo and script

-Customer references

As part of the category story certification process, also create an internal bill of materials for sales enablement, including:

-Category elevator pitch and walk through of the customer presentation (think of it as the Director's Cut version)

-Category mapping to initiatives, use cases and persona value, including customer case studies

-Competitive battle cards & Proof of Concept lockout documents

Remember, defining a new category will also place your company alongside a new set of competitors who are likely dominant players in the market, so it’s important to educate the field on both existing and new competitors.

Rule 4: Agree On What to Measure

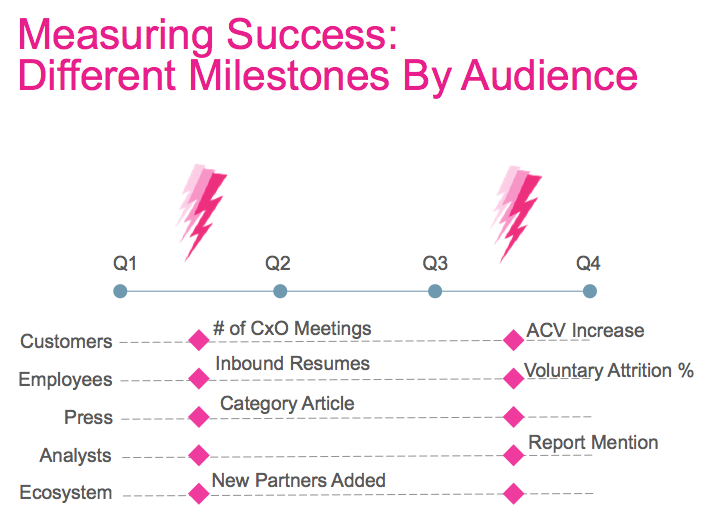

You’ve launched the category and executed your lightning strike. Maybe even a few lightning strikes at this point. Now comes the billion (hopefully multi-billion) category design question: How do we know it’s working? It’s critical to get agreement across the entire executive team on how you will measure success, including the metrics and goals upfront, otherwise the CMO will share metrics as part of their marketing update and it will inevitably wind up in a debate as to if category design really was the driving force that moved the needle vs. other factors such as new product introduction or better internal execution. To avoid this and create accountability across the entire team - metrics and goals should be set along each side of the category design triangle. While these will be specific to your organization, some examples include:

Company Design: this could include both top line revenue and market share metrics, as well as the impact on non financial metrics such as talent acquisition and retention.

•ACV Increase

•CxO Meetings

•New Logo Wins in Key Verticals

•$1M+ Deals

•Renewal Rate

•Market Share Increase

•Recruiting Win Rate

•Voluntary Attrition Rate

Category Design: this should focus on marketing related metrics illustrating a shift with key influencers.

•Category Articles and Share of Voice in Tier 1 Publications

•Analyst Report Category Mentions or New Reports

•CxO Category References

•Job Titles or Descriptions Referencing the Category and Skills Required

Product Design: this should encompass both your product and partner ecosystem roadmap, including any technology required to fulfill the full category vision (hint: it will never be just you).

•Rate of Product Releases: New Innovation & Functionality Gaps Filled

•Competitive Win and Displacement Rate

•New Ecosystem/ Integration Partners

A good framework for thinking about measuring success over time is to map out each key stakeholder - including prospects, customers, journalists, bloggers, industry analysts, investors, etc. - and create a froto (from/to) map with category design measurement aligned with each stakeholder. For each stakeholder, understand the following:

-Current (from) state of where they are today: existing perceptions of the problem, if they even know there is a problem, and how to solve it

-Future (to) state of where you want them to be: the new problem you want them to have, how you want them to view the problem, and belief that your company and product are the best and only ones to solve it.

-Measurement of success: the metrics and goals so you know how well you are doing in moving each audience, and where they are on the curve.

Once you have the frotos and metrics for each stakeholder identified, create milestones aligned with each lightning strike to track movement over time along the curve. Make sure your goals are realistic based on the audience, the distance between the from and to state for that particular audience, and the effort required to move their beliefs and perceptions. For example, getting a category article published in a Tier 1 business press outlet at category launch may be a reasonable. Journalists pick topics to write on based on what’s newsworthy and market-moving, and have more flexibility in what they write and when. On the other hand, it may take a couple of lightning strikes over the course of a year to get a mention or inclusion in an analyst report, especially if the category is prescribing a change from how analysts currently view and cover the market. They may have stronger beliefs based on the current view of the market versus the market shifts that your category lays out. One of the most important traps to avoid is not claiming category design victory until a Gartner Magic Quadrant is created for it. Changing the scope of an existing MQ or creating a new one altogether will likely require a long-term, multi-year relationship, and may not happen at all. Just make sure to set realistic goals and educate your internal stakeholders on what is reasonable. Below is an example of how to create milestones for measurement aligned to each lightning strike by key audience.

Questions? What are the best practices or pitfalls to avoid that you have experienced in your category design journey? We’d love to hear them.