The 6-10 Law: How age and money impact start-up value creation

Over the last decade in Silicon Valley there has been a building sentiment that, “the more money we raise and the longer we stay private, the better off we are.” We wondered if data science research could reveal something

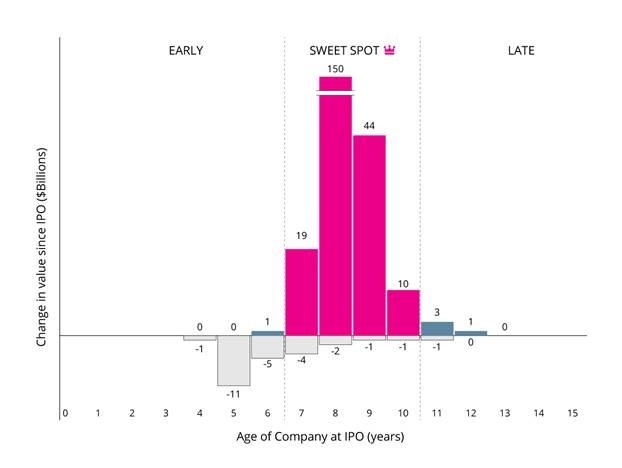

So, we analyzed the total value created by every technology IPO from 2000 to 2015, and found something remarkable. [1] We found a consistent “sweet spot” window. The data show that the best time for a company to go public is when it is between six and 10 years old. Oracle, Cisco, Qualcomm, Google, VMware and Red Hat are among the many enduring category kings that went public in the sweet spot window.

We found that the age of a company at IPO even mattered more to post-IPO value creation than the amount invested in a company while it was still private. Seriously!

More amazing, we discovered that there is zero correlation between the amount of money raised by a company before it goes public and its post-IPO value creation. Zero. Legendary tech investor Jim Goetz of Sequoia Capital goes so far as to say, “The more money you raise, the less value you create” — clearly suggesting an inverse relationship between how much a startup raises and enduring value created. That blew our minds. The only consistent factor in the data that mattered to create enduring value in our study was the age of the company. Huh?![2]

That made us wonder if there might be a connection between how quickly new market categories form and develop and the six to 10-year-old IPO sweet spot.

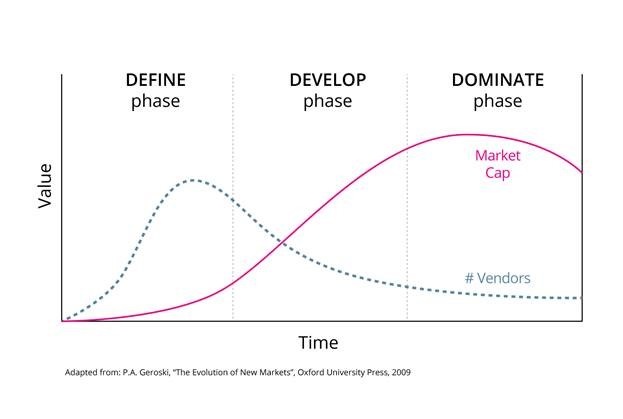

We got an aha when we looked at the research of Paul Geroski, author of “The Evolution of New Markets.” Geroski’s research explains the stages in the evolution of a new market — that is, a new category. In a market’s earliest stage, the number of companies in the space explodes. This is the phase when the new category is first defined and a gaggle of entrants are scrambling to solve the problem.

In the middle phase, the number of companies dives as the king emerges and competitors disappear (because this is when the category king normally starts sucking up all the economics).

In the last phase, the number of companies bottoms out as the king dominates and reigns over the market. Inspired by his work, we created the category lifecycle model (see Fig. 1).

Now, as Geroski also showed, the market value of the whole category rises slowly in the first stage as a category gets on its feet, then like a rocket in the middle stage as the category catches on. In the last stage — the domination stage — value peaks and then tails off as the category matures.

Right in the middle of the category lifecycle model, the two lines — number of vendors and total category value — cross. Those lines cross when a category takes hold, a clear king emerges, the public understands the problem and solution and investors pour money into the category and its king. It’s the moment of category explosion.

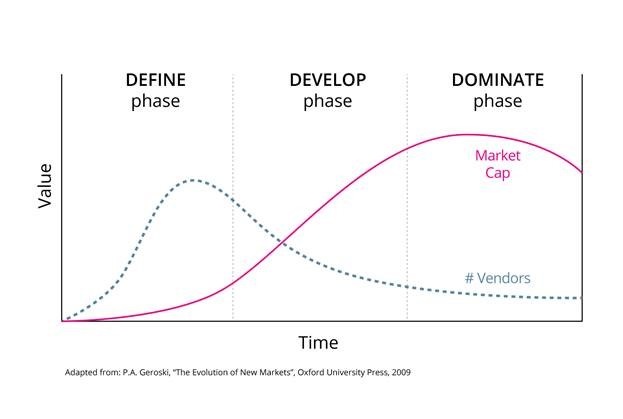

Let’s go back to our sweet spot research. We overlaid it on the category lifecycle model and saw that the sweet spot lands right around the moment Geroski’s lines cross [see Fig. 2.)

That seems to show that the best time for a category-creating company to go public (our data) and the moment of category explosion are the same. And in the post-internet era, that’s consistently been about six to 10 years after the first companies are founded in the category.

This is the 6–10 law.

What does all this mean for CEOs, founders, executives, investment bankers and venture capitalists? If you want to build a stand-alone company that creates enduring value, you have six to 10 years to design a new market category, emerge as the category king and get public. That’s what the data science says about tech startups playing bigger.

Play Bigger book coverEditor’s note: Play Bigger: How Pirates, Dreamers, and Innovators Create and Dominate Markets, by Al Ramadan, Dave Peterson, Christopher Lochhead and Kevin Maney (HarperCollins, 2016) was released today. Winning isn’t about disruption anymore; it’s about creating a category and becoming the category king. This is the how-to guide for building a legendary company.

Endnotes:

- At the time we did the study, we found 4,424 American venture-backed technology companies that had raised a Series A* since 2000. Of those, 69 made it to IPO.

- We showed our findings to a number of top VCs and investment bankers, and this pretty much sums up their reaction. They were stunned.