The technology industry has what you might call a “Cosby”—a dark secret that undercuts its image.

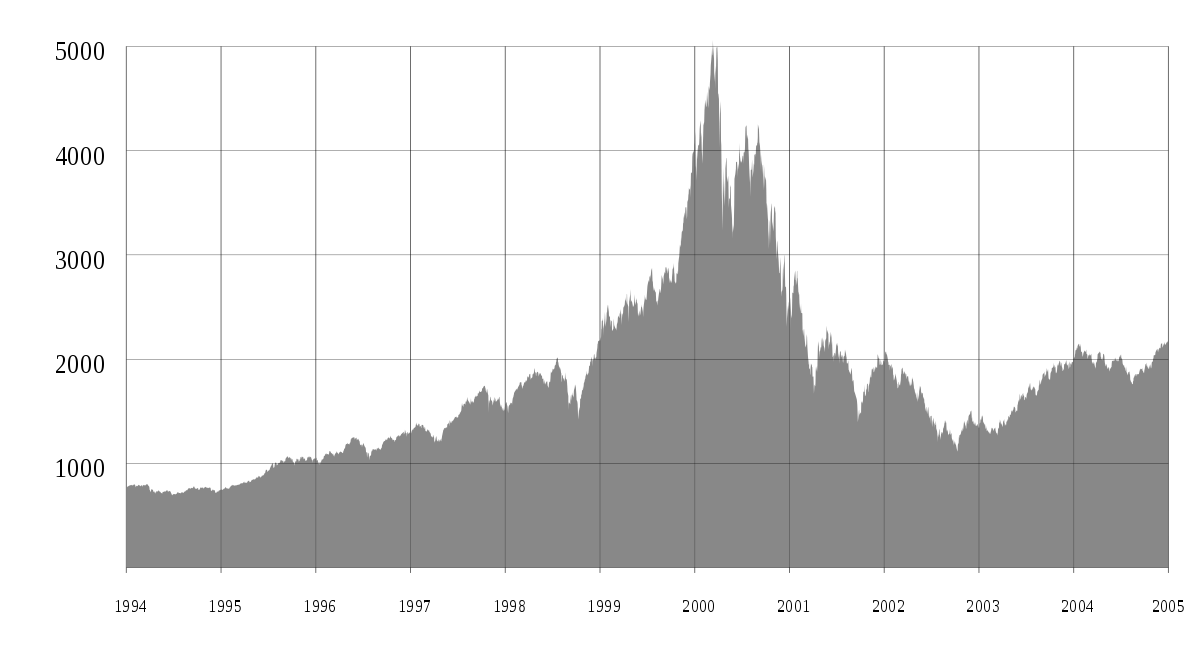

Tech on the surface looks bubble-hot. Valuations can seem crazy: WhatsApp was bought for $22 billion, Uber is worth $41 billion, Alibaba has a market cap of more than $250 billion. If this feels too much like 1999, then at the first sign of trouble you’d expect the exuberance to collapse like a straw house in a Buffalo snowstorm.

But the industry’s dynamics have changed in recent years in ways that suggest we’re not so much seeing a bubble as a shift in tech’s wealth distribution. It’s a startup version of the wealth gap. Everything goes to the top 1 percent.

So the Cosby is that below the top tier you’ll find a whole lot of striving and desperation—a burbling stew of stagnant companies, founder angst and money-losing investments. The winner in a particular market space—like Uber in on-demand rides, Airbnb in short-term stays, Facebook in social networks—takes nearly all the economics in that space. Losers get scraps. Tech is definitely red-hot, if you look only at the winners.

And the separation between winners and losers happens faster than ever. Companies have to race like hell to define and dominate a space before someone else does—hence the founder angst. This is borne out by a new study by Play Bigger, a Silicon Valley advisory firm. (Full disclosure: I helped write the study. Play Bigger did the number-crunching and analysis.)

The study, which analyzed valuation data on thousands of tech startups, found that winning companies born since 2009 get to super-high valuations three times faster than companies started in the early 2000s. Looked at another way, this says that if a company is going to reach a $1 billion value, it will do so in one-third the time that climb typically took just a decade ago.

But this rising tide floats the yachts and sinks the dinghies. Only 80 companies started since 2000 have hit $1 billion in value. Those are the companies we read and cluck about.

And in most cases, only such top-tier players get the explosive growth and searing envy. Of the 80 companies that hit $1 billion, half are what the study calls Category Kings—companies that define and dominate a new category of business. Uber, despite all its Biff from Back to the Future behavior of late, is a good example of a Category King: It helped create a new kind of business, took the lead in defining it and became the dominant player. A Category King typically takes 70 percent of the total market value of its category. All the rest of the entrants split the remaining 30 percent.

Even worse news for the second-tier companies: The study found that a six-year-old startup that isn’t yet a Category King has almost zero chance of becoming one. Hundreds of companies are left to forever survive, like raccoons at a summer camp, on their category’s scraps. That explains why Uber was valued at $41 billion earlier this month, while at about the same time the No. 2 in that space, Lyft, was valued about 40 times lower, at $1.2 billion. The rest of that category is barely noticeable. Investors look at the future value of that category and see one company taking most of it.

The Play Bigger study puts some data behind the provocative advice investor Peter Thiel doles out in his book and lectures. Competition is for losers, he likes to say. The goal of any startup is to become a monopoly in its space. In the tech business, you’re either a 1 or a 0, and in a given market there’s only one 1. Everyone else winds up with a tax write-off and some coffee mugs with an extinct logo.

Why, then, do so many very young startups get buckets of investor money? As a new category first congeals, a handful of companies can look like potential kings. Investors at that stage bet on a potential king and pump in millions of dollars to try to quickly vault it into the lead. A company like Yik Yak (sounds like something I do after a drinking binge) got $62 million from investors after 13 months in existence. Yik Yak is trying to win a nascent category: anonymous messaging. Its investors aren’t insane—they know they have to invest big and fast to get Yik Yak to the top of the category before another company gets there.

Those investors will either win big, or lose big. Once a category’s winner has emerged, investors fight to get their money into that company, driving up the valuation. At the same time, the losing companies turn into investor kryptonite. Just look at Fab, which fueled Silicon Valley bubble-bursting anxieties last month when it was valued by a potential buyer at $15 million just a year after raising $150 million. Investors piled into Fab when it seemed to still have a chance of defining and dominating a category, then ran for the hills when that chance seemed to evaporate.

The forces that drive this dynamic will only grow stronger. Global networks and social media allow everyone to quickly find and adopt the best in any category and flock to the winners. There are about 3 billion people on those networks now, and that pool is growing 6.6 percent a year. In one category of business after another, the trend will continue to swing toward winner-take-most.

As with Bill Cosby, tech’s secret isn’t exactly new, but it’s getting harder to deny.