CATEGORY IS THE NEW STRATEGY

Al Ramadan

Dave Peterson

May 16, 2017

An updated extract from Play Bigger. How Pirates, Dreamers and Innovators Create and Dominate Markets.

An earlier version of this article appeared in chapter 2 of our book Play Bigger.

THE CATEGORY LIFECYCLE

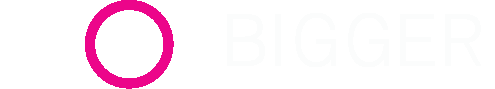

Paul Geroski, author of The Evolution of New Markets, was an inspiration for some of our thinking. One of Geroski’s charts shows the stages in the evolution of a new market—that is, a new category. In a market’s earliest stage, the number of companies (he calls them providers) in the space, explodes. This is the phase when the new category is first defined and a gaggle of entrants are scrambling to solve the problem. In the middle phase, the number of companies dives as the king emerges and competitors disappear (because the king starts sucking up all the economics). In the last phase the number of companies bottoms out as the king dominates and reigns over the market. We adapted his work and created what we call the Category Lifecycle see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Category Lifecycle

EVOLUTION OF CATEGORIES OVER TIME

In our lectures and consulting work we often get asked the question of whether new categories emerge out of old categories and how do categories evolve over the long haul.

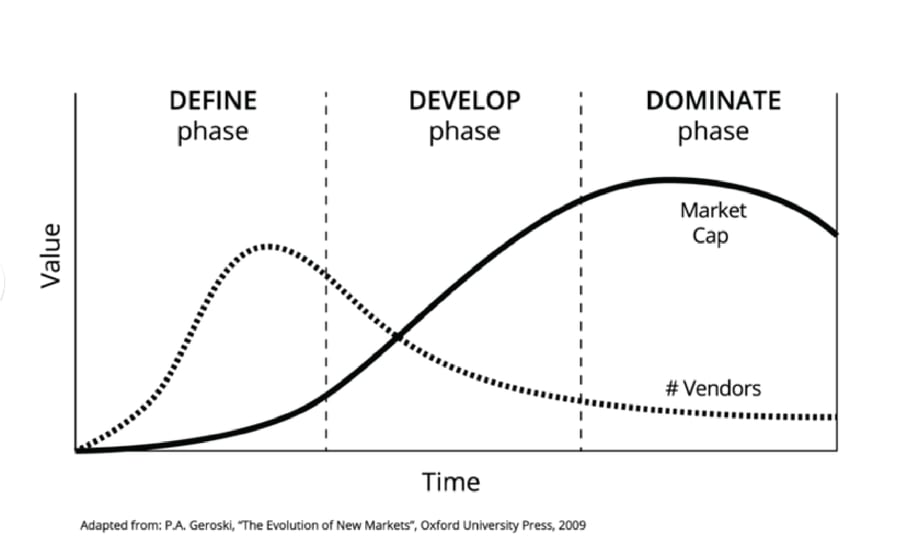

We contracted with Opus research to develop a timeline for the CRM category as a starting point for this discussion. See figure 2.

Figure 2: The Evolution of the CRM Category

In the very early days of business, we used to write contact details into our Rolodex. A piece of cardboard filed in a rotary file. When we had a new contact we took a blank rolodex card and wrote their name, address and phone number on the card and filed the alphabetically. If we needed to contact someone, we would find the person’s Rolodex card and then we would call them, usually on a rotary phone bolted to a wall.

With the advent of personal computers, the rolodex got loaded into a new category of software we called Contact Management software. ACT and Goldmine were the category leaders and built wonderful businesses on that back of the PC revolution.

As PC’s got networked and folks within an Enterprise wanted to share contacts, client server software emerged to allow a centralized repository for contacts. In addition the innovators allowed users to add notes about calls and discussions with these contacts into the database. These innovations led to the emergence of the Sales Force Automation category. An exciting category that was led by Brock Systems. Every company needed a SFA solution and a $X billion category exploded.

While it was important to capture the discussions and sentiment during “sales calls” it became just as important to capture service calls, call center discussions, field service calls and other meaningful interactions with customers. Tom Siebel single handedly aggregated all these customer touchpoint systems into a single category he called Customer Relationship Management. Pretty much every Enterprise in the world rushed to implement a CRM system chasing the holy grail of managing their customers experience. Unfortunately these systems

were very difficult to install because of the nature of client server computing and the underlying software architecture.

In the early 2000’s along came a brilliant category designer called Mark Benioff. He believed in a new technology architecture called Application Service Provider (ASP) and a business model called Software-As-A-Service (SAAS). Both of which evolved into the Cloud. He evangelized a problem describing the failed Siebel installations and proposed a new vision – CRM as a service. You could just buy CRM by the feature and seat without installing any software. It was so successful that it crushed Siebel and led to his company, Salesforce, becoming a dominant leader in CRM and the cloud categories.

But the story doesn’t end there... There are a dozens of entrepreneurs, born of the mobile and social revolution, who are re-imagining what CRM actually means in this now social mobile big data era. That story is yet to be written.

Categories are not static. They continue to evolve as the underlying technology, consumption medium and channels, and use cases evolve. The lifetime of some of the great categories can be well in excess of 10 years.

Value Creation and the 6-10 Law

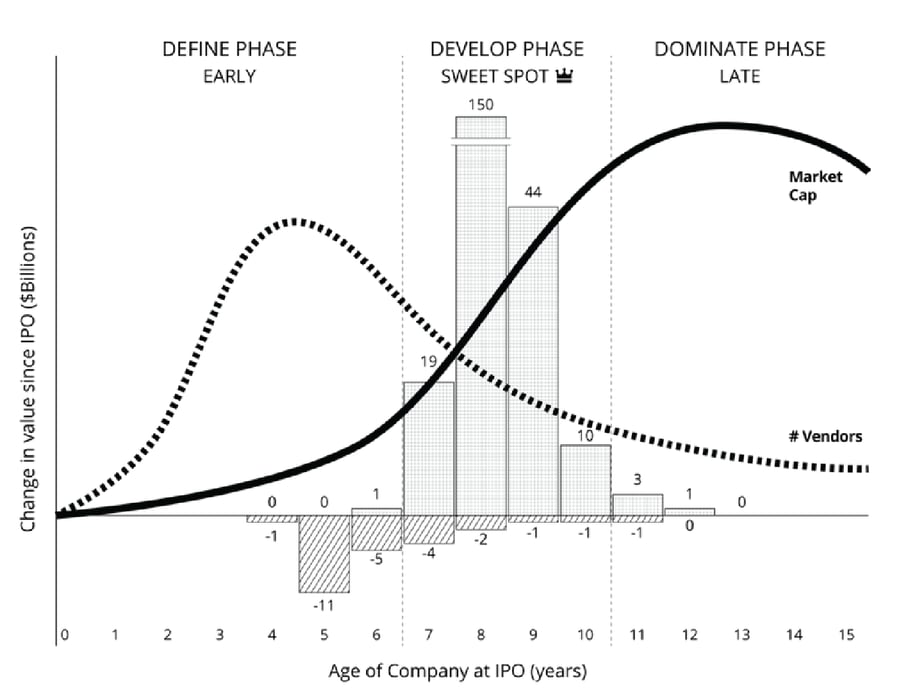

Let’s go back to our 6-10 Law. This research showed us that companies that go public between the age of 6 and 10 years created more than 95% of the market cap for all technology companies founded since 2000.

We overlaid it on the Category Lifecycle and observed that the IPO sweet spot lands in the develop phase of the category lifecycle. See Figure 3. This seems to show that the best time for a category-creating company to go public (our data) and the moment of category explosion are the same.

And in the post-Internet era, that’s consistently been about six to ten years after the first companies are founded in the category. (Pre-Internet, categories took a little longer to spread throughout a market. In 1986, Microsoft went public in its sweet spot, and it was thirteen years old.)

Figure 3 // IPO Sweet Spot Overlay

Figure 3 // IPO Sweet Spot Overlay

We asked some of the leading investment bankers why the develop phase of the category lifecycle is so important. George Lee from Goldman Sacs was one of the first people we spoke with about this research. He said the develop phase of the category lifecycle curve is really interesting to public investors because two of the most important things these investors look for are growth and expanding margins. In the develop phase we see rapid adoption (revenue growth) and most vendors dropping away (increase in pricing power leading to expanding margins). So it makes complete sense that the category kings that go public during the develop phase of the category lifecycle share that value creation with the public markets and go on to dominate it.

While the principals of technology adoption have been explained well in books such as Crossing the Chasm or Gartner Hype Cycles, we wanted to explore more of the drivers of adoption and turned to some of the leading researchers in brain science. What we found was that changing perceptions of users and buyers are key to adoption and the reason the 6-10 law exists. Said another way, it often takes 6-10 years to change the minds of buyers and users.

Brain Science

The ideas behind categories and how customers organize their buying decisions have been understood for some time. Even in the 1970s, Ries and Trout described how, “[t]o cope with complexity, people have learned to simplify everything.” They added: “The ranking of people, objects, and brands is not only a convenient method of organizing things but also an absolute necessity to keep from being overwhelmed by the complexities of life.” (Amazing, right? People in the seventies were overwhelmed! A real-life Austin Powers, frozen since the sixties and revived in the 2010s, would blow his brain’s circuits by just walking into a Costco or looking at an iPhone App Store.) And even back then, as Ries and Trout explained, marketers knew that winning a category meant everything. “History shows that the first brand into the brain gets twice the long-term market share of the No. 2 brand and twice again as much as the No. 3 brand,” they wrote. “And the relationships are not easily changed.”i

What’s different now, though, is the sheer magnitude and velocity of this dynamic. The 1970s saw, compared to today, few new products or new categories because barriers to entry were so high. New products—almost always physical in that non-digital age—had to be manufactured and distributed. Getting the word out involved buying costly advertising on TV or in print. Today, an offering like Slack or Snapchat can be built by a handful of people in someone’s basement and distributed globally through the cloud with one mouse click. If people like it, it goes viral on social networks. No need to buy $30 million Super Bowl ads. The complexity Ries and Trout described has gone exponential, which makes the need to categorize more powerful than ever. Few people have the time or brain capacity to make buying decisions any other way. So people look for ways to make fewer choices in the face of more choices.ii “Increased choice among goods and services may contribute little or nothing to the kind of freedom that counts,” writes Barry Schwartz in Paradox of Choice. “Indeed, it may impair freedom by taking time and energy we’d be better off devoting to other matters.”iii

The category as an organizing principle is supported by research on the brain and cognitive biases, as described by Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, and by a host of brain scientists.iv Our brains are governed by more than fifty different cognitive biases that push us toward decisions based not on facts and logic, but on instincts that can be at odds with facts and logic. It’s a shortcut system in our brain—a way to make decisions faster and easier, especially when overwhelmed by too much information.

One of the cognitive biases is called the Anchoring Effect. It’s a tendency for an early bit of information to affect our view of all the information that comes after. For instance, the first offer put on the table in a negotiation has a powerful impact on any other offer that comes after. So in category dynamics, an early company that solves the problem will win a powerful place in customers’ minds. It becomes an anchor. Other companies coming afterward get judged against that early company. Another bias that kicks in is the Choice Supportive Bias—the tendency to give positive qualities to an option we’ve chosen just because we’ve chosen it. This means that once you’ve committed to a product or service in a new category, you’re likely to feel certain that it is the best even if something slightly better comes along. This helps explain why category kings can’t be dethroned by a competing product or service that’s simply better. Once people have chosen a king, they will always tend to believe the king is better, even if it’s not. This reality explains why companies with superior technology can still lose category wars. Once a king emerges customers believe it’s the best, regardless of any evidence to the contrary.

The category king concept also plays out in humans’ pack mentality. Groupthink Bias describes a tendency to believe things because other people do. Brain studies have shown that when we hold an opinion that differs from others’ in a group, our brains produce an error signal, warning us that we are probably wrong. In a category, the Groupthink Bias brings momentum to an emerging category king—customers embrace the king because so many other customers have embraced the king. For some people the pressure to make important buying decisions is not unlike the feeling of being under threat. Research from Vladas Griskevicius at the University of Minnesota shows that when people are threatened they seek safety in numbers. “In the pack we feel less vulnerable, less likely to get eaten when the critter cannot see us because we blend in with the crowd. The group is our haven, our shield.”v As result, the people who already

own iPads make the people thinking about buying iPads feel safer about the decision. The need to fit in is a uniquely human behavior and begins as early as two years old. “Conformity is a very basic feature of human sociality,” said Daniel Haun, a psychological scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.vi Studies show that people will and do change their minds to fit in. MRI scans of people changing their minds to conform to a group show that two critical reward-related regions in our brain are stimulated when we change our minds to be like others. It turns out we want to buy from category kings because our brains feel safe and happy when we do.

Category thinking works because it’s the way our brains work. More important, it’s the mode of thinking that our brains turn to when faced with exactly the kind of overstimulated, crazy-ass marketplace we have today and will have in spades in coming years.

REFERENCES CITED

i Ries and Trout, Positioning, 31–43.

ii “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to choose.” No . . . wait . . . maybe that’s “lose.” Never mind.

iii Barry Schwartz, The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), 4.

iv For this paragraph, we tip our hat to two sources. One is the marvelous book by Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), and the other is Cris Evatt’s Brain Biases blog, http://brainshortcuts.blogspot.com/.

v Michelle Wick, “Safety in Numbers,” Psychology Today, July 16, 2013. https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/anthropocene-mind/201307/safety-in- numbers

vi Lecia Bushak, “Conformity Is Unique to Humans, Integral in Most Social Interactions, and It Begins as Early as 2 Years Old,” Medical Daily, November 1, 2014. http://www.medicaldaily.com/conformity-unique-humans-integral-most-social- interactions-and-it-begins-early-2-years-old-308886.